Here’s how it went. I ran into one of the cute couples on station as I moved my sheets to a dryer in preparation for my departure the following day. They were scheduled to leave at the same time. I knew this because she’s French and a regular scientist here but despite having done something like six seasons (or because of it) she’s as excited as I am to be off the Pole and back to civilization. (Yes, it’s largely the food.)

Anyway, the cute couple say they’re leaving immediately because the weather looks iffy for tomorrow and for Thursday, with clearing on Friday. I’d heard the same dire rumor—gossip about weather flies in a closed community.

I was not going to languish at the South Pole—gorgeous and magical as it is—for an extra two days if there was something I could do about it. Up I march to station management. There, I ask as politely as possible whether it’s possible to leave a day early. (I can be very polite when I choose to be.) The woman in charge shakes her head as she heads down to ask the head of cargo, a woman two doors down sporting excellent aviator style glasses. It’s her job to decide these weighty matters. The answer is no, lots of people have been asking and it’s too late to change the days given all the work of moving bags, changing manifests, etc. I smile calmly and say okay, I understand. I walk down the hall with the manager and ask her as nicely as possible to let me know if anything changes. Sure, she says, apologetically.

Before I know it, the woman with the terrific glasses emerges from her office. She concedes she has one seat on a later flight if I can be ready with all my bags in half an hour. This single availability is determined by the number of survival bags on the flight—the bags I noticed on my Basler flight in that contain a tent and maybe some crackers and water so that if the plane goes down on the barren icy continent, say somewhere really hospitable like the Beardmore Glacier, passengers have a prayer of surviving for an hour or two.

In short, she says if I can be ready to bag drag in half an hour I can go. I assure her I will be there and on time. Then I practically sprint down the hall to pack up my room, gather the last of my still-damp laundry, move items around to make sure I have what I need in my carry-on in case my bags disappear into cargo but I don’t end up flying. It doesn’t sound like a lot but it is. There are several important stray items hiding in the backs of my drawers that I nearly leave behind in my madness.

I make it to my bag drag appointment at 11:30 AM, weigh in right on the money at the limit of 85 lbs. for my three checked bags. (I’m bringing back two bottles of Pole water—one from fresh snow and one from the tap that’s produced from ice formed circa 1500 AD. I mean, how cool is that? Very, I say, but also a bit heavy.)

After my bags disappear across the frozen glacier, I have three hours to sprint around station finishing all the things I thought I had more than a day to complete. Every time I see someone, they’ve heard I’m leaving so they want to chat and exchange contact info and I want to do the same even if I still have library books to return, sourdough starter to spoon into a jar, a bed to strip, a room to dust and vacuum, my “Welcome to the Pole Cree” sign to throw in the corrugated recycling bin and skis to return to the shed out back. I’m losing my mind but excited. One woman, a stewie wants to leave on the same flight but has been told no, glares at me. It’s fitting. She’s been glaring at me all season for no reason whatsoever. For the first time I enjoy knowing why.

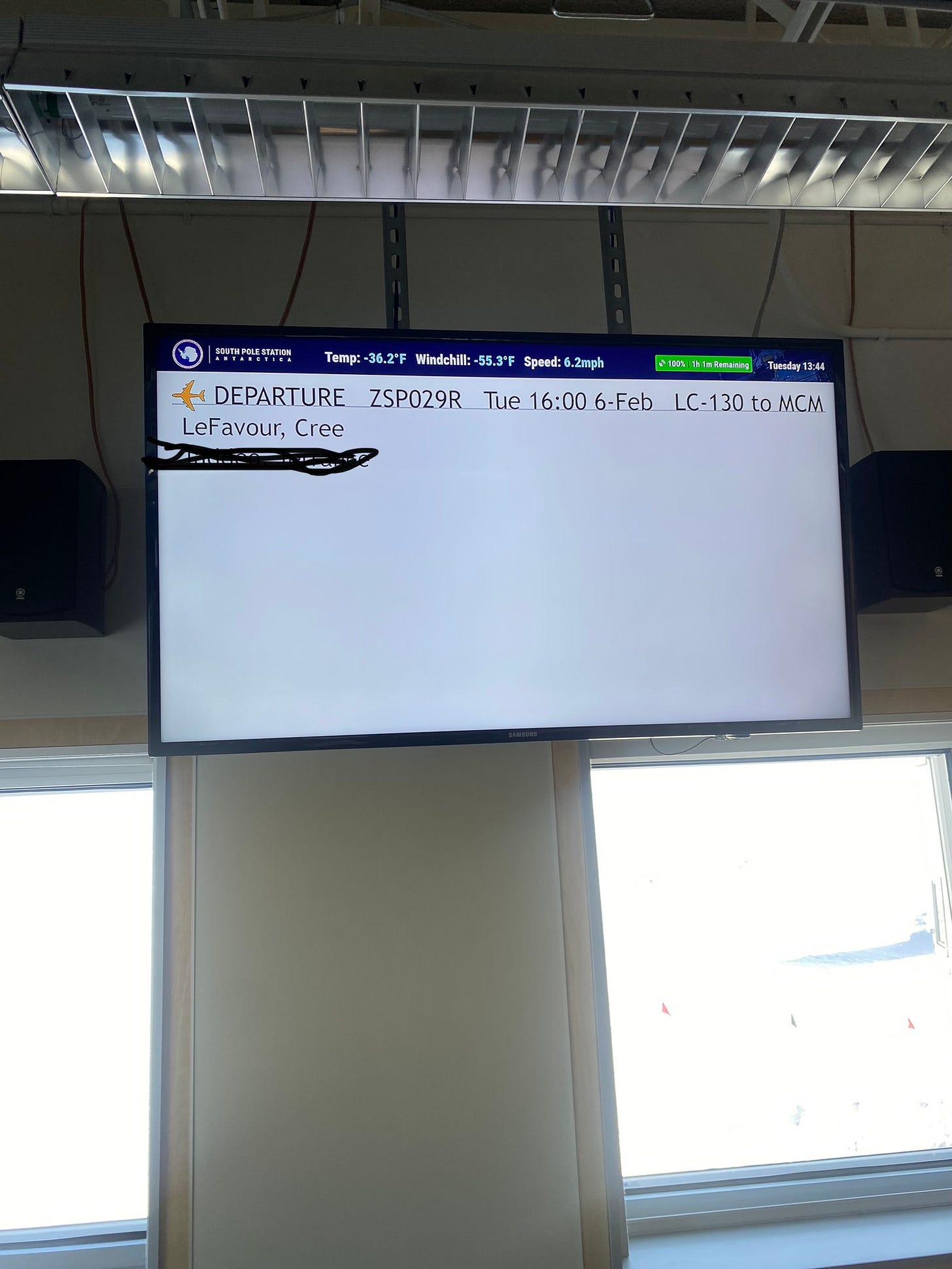

By the time I’m finished I’m sweaty and feeling a tad panicked, as if I’m late for an international flight. I would never be late even for a domestic flight and I’m not late. In fact, I have time to shower one last time in the water from 1500 AD that gushes up from the Rodwell. Lathering my hair, I think about penguins rather than where the wastewater is headed. Back in the galley, I stare up at the manifest. There’s my name—I really am leaving the South Pole and it has all happened so fast I’m breathless with anxiety and excitement

At one moment I had a leisurely day and a half ahead of me to wrap up my South Pole adventure; the next I was on the way out. I’d been working on being a human being again—not a ghost or an automaton. True, I’d already dropped off my atrocious uniform in the laundry room and deposited my stinky kitchen clogs in the Skua shed for some other unfortunate kitchen soul to claim. Work, sleep, work, sleep. The routine has worn me down, stilling my brain into a mushy combination of audiobooks, podcasts, small talk and recipes that mix as poorly as cold eggs and butter. All that said, I’ve also made handful of friends. I can count them on one hand, but it takes the whole hand. That’s not half bad.

My colorful carry-on bag overflowing, I stand at DZ (Destination Alpha) clad in the required ECW (Extreme Cold Weather) to await the plane. I am wearing my very chic white bunny boots. People I like pop by to say one last goodbye—my mechanic friend leaves work and arrives for a hug smelling of fuel and axle grease. I adore her just as I adore my NOAA friend who gave me the snow from the clean sector, my friend from IceCube who sent me off with more than my share of the fleece hats, and a friend I had sushi in Christchurch with way back, what seems like ages ago, on the way in. Crucial friends are missing—but I’ve said good-bye to most. After photos—which I can’t show because of agreements not to name or post photos without permission—I take my bag outside to watch as the fuelies gas up the C-130.

Half an hour in the 38° F below cold and I’m worrying about the state of computer and my South Pole sourdough mother. I remove both items from my bag and tuck them under my coat to keep them from freezing—sure death to a lithium battery as much as to the busy bacteria I’ve nurtured since November. I have a little baggie of rye flour to feed the beast on the long journey home—it looks a lot like what I imagine a great deal of refined heroin might look like but I can be sure it won’t turn the sniffer dogs on.

Standing there in the glare that’s been with me for four months solid, I imagine the otherworldly days ahead, the variety and change that awaits after the stasis of the South Pole. Other than seeing family, friends and my dog, I dream of darkness.

The bracing white light piercing the galley windows at all hours, including all night as I beat butter, sugar and eggs, shaped rolls, frosted cakes and filled pies made it easier to be awake but I haven’t seen a star or the moon or a sunrise or sunset for four months. There’s a relentlessness to the endless sunlight reflecting off the snow. At the beginning I found the bright light cheerful but it has begun to wear me down with its insistence on daytime’s go-go-go energy. I’ve never really thought about nighttime as a potent force on my mood, but I feel it here as I try and fail to find somewhere to hide. My room with the cardboard barrier in place to block the light is all I have if I want the restfulness of a dark room.

Night conjures and perhaps even induces a letting go, even a certain hedonism to mark the finish of a day—eating and drinking to excess, with dinner and bed to follow, the morning sun erasing shadowy sins. I long for a loosening of the discipline of my life at the Pole as the memories of delicious food, wine, conversation and the profound pleasures of indulging in them with family and friends, dog on lap, have grown larger.

I can almost feel myself there at table with my people, the meal finished, the wine bottles piling up, a runny cheese on the table, crumbs littering the tablecloth, my pretty dishes and glasses stacked next to the sink. In this vision, the warm glow of my cozy dining room contrasts with the dark New York night beyond, the reflections of colorful neon signs lining Broadway casting their colors. The night in New York jingles with the relentless sound of city life—voices, sirens, cars, the rattle of the subway—sounds so alien to me at the Pole that I can no longer hear them in my head even if I remember their existence.

I’m good and chilly by the time one of the camo-clad men from the New York National Guard waves us toward the plane. I feel sad and ecstatic at the same time. I can’t quite believe I’m leaving this stunning landscape behind but it’s not my home and I miss the person I was before I came here. Being “the baker” for as long as I’ve been known by that job title confuses my sense of self. I’m pretty sure the self I recognize is waiting, back at home along with a tight deadline for a new memoir and a (still!) unsold novel

The monster plane must be drunk with fuel, the cargo loaded into the back end that opens wide enough for a ‘dozer to place pallets directly into its belly. I walk with the other passenger—he’s a NASA VIP day-tripper—around the cartoonishly round nose of the gorgeous machine. Above me the rotors whizz mightily—they’re more than a little frightening; magnificent in their antique power. The roar deafens even through my snug silicone ear plugs.

The seats are similar to the sling seats you might take camping. I settle in—the heat cranks as the engine revs. I feel the plane race down the snowy runway I’ve walked along many times, marveling at my presence at the South Pole. As the G-force pushes me to the back of the plane—and pushes my neighbor onto me—I thrill as I feel the lift, the smoothness of air. I’m at once happy and sad. I’m pretty certain this is goodbye forever to The Most Beautiful Freezer in the World.

Once we’re aloft there isn’t, alas, much to see. So I contemplate, once again, my future. Upon my return to civilization I look forward to the most basic pleasures: grass on my feet, air that’s humid and rich with varied scents, plants and flowers, walking into a grocery store to buy whatever I like, petting and talking nonsense to dogs and cats, eating all the fresh food, drinking a potent flat white, cutting into a rare steak that hasn’t been frozen since the Carter administration, that long hot shower I wrote about in my previous post, sitting in a café to write….the list goes on and on. But before I do any of that, I’m determined to see a penguin in the rough.

As I step off the plane at Willie Field it’s there, on the sea ice. Amidst the shacks and sheds and C-130s and NSF (National Science Foundation) vans the lonely bird sits, waiting out the process of molting next to a bicycle (!). I sympathize with its discomfort as it changes its feathers as much as with its dislocation.

.

Thank you for sharing your journey.

I have so enjoyed your dispatches. Safe journey home.