I have my ice date, I have a ticket, I really am going to Antarctica....

On packing, traveling and saying good-bye

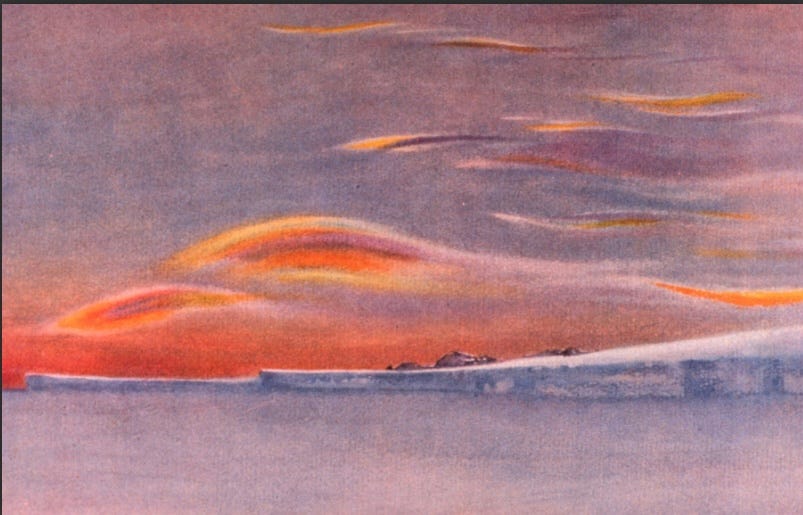

Watercolor drawing from Hut Point by E.A. Wilson. First printed in Scott’s Last Expedition (1913).

I have an ice date! I am really and truly going to Antarctica and now that it’s imminent—I fly out of JFK on Sunday, October 8—I’m freaking out. Weirdly, my crazy, moon-faced excitement is, for the first time, tempered by the reality of what I’m doing: going to live and work in Antarctica for four and a half months. If you read my first post you know how and why I get myself into this. (If not, maybe go read it?)

To clarify, Sunday is not my ice date. What is an “ice date” you might reasonably ask. In United States Antarctic Program (USAP) parlance it’s the day a person is scheduled to touch down on the continent of Antarctica, which generally means McMurdo Station. In my case I’ll be leaving New York’s JFK Airport, known as my AOD (Airport of Departure) five days before my ice date because it takes a full day to fly from New York to Christchurch, New Zealand AND I’ll be losing a day thanks to crossing the international date line. I leave on the 8th, I arrive on the 10th. It’s a 17+ hour flight. Go figure. The remaining time before my ice date will be spent in Christchurch. On day one I’ll be allowed time to simply sleep in a proper bed—boy will I need it. USAP takes care of every detail—they’ve booked me a hotel and will pick me up the airport. They’ve also arranged the visa I’ll need and the permissions required to enter New Zealand bearing the big red flag that is a one-way ticket. After I get some sleep I’m scheduled for various orientation and training sessions, Covid testing, baggage sorting, uniform and gear issue plus other things I don’t yet know about.

I suppose my shock at finding myself with a plane ticket several days before my departure is understandable. Until yesterday I was uncertain whether I’d manage to get to McMurdo in advance of the late October start of the South Pole season at all. Amidst the crush of bodies headed south all at once there seemed, for a time, a good chance I might not squeeze onto a flight. Wildly speculating about the cause, I concluded it must be the “ice flights” causing the bottle neck. Those are the military flights from Christchurch, New Zealand to McMurdo Station that carry humans and cargo. That said, take my guess as you will, coming as it does from a first-time deployer (how very military that sounds!) who really doesn’t know one way or the other precisely what’s involved in getting all the goods and people to Antarctica for what’s called “main body” or peak summer season for the National Science Foundation (NSF).

I figured bureaucracy mixing unpleasantly with the famously temperamental weather on Ross Island must explain a great deal. From what I understand, pileups in Christchurch occur with maddening frequency. Why? Because when one of the military cargo planes leaves Christchurch it’s often forced to turn around mid-flight if/when the weather changes, 2435 miles away, at the ice landing strip that constitutes McMurdo’s “airport.” When the plane is forced to turn back it’s called a “boomerang.” To prepare for this eventuality I will have a specially marked “boomerang bag” containing the items I’ll need to spend another night—or several—back in Christchurch, waiting for the weather to clear. Meanwhile, my regular “checked” baggage will, presumably, sit in a big heap either in the plane’s hold or in a hangar nearby.

A boomerang can happen multiple times in a row. Antarctica is the windiest continent on earth. As a result, weather—blowing snow, sleet—at the coast comes and goes rapidly. Both Antarctica and Greenland have what are called katabatic winds. As a non-meteorologist, I can say with confidence there are more factors involved in this phenomenon than I’m qualified to discuss but I do grasp how cold air generated by interior ice shelves falls (blows) down toward the lower, warmer, moister coastal areas where the air is rising.

I don’t really mind if I boomerang—even if it will make for a very long flight. It strikes me as part of the romance of adventure. I’m actually going is all I can think about even if in some way it hasn’t entirely sunk in. I’m still home on the blue velvet sofa with the dog stretched out on the back cushion in the sun, coffee at my elbow, novel not sold. For the past four weeks since my first post, as I waited for my EBI (extended background investigation) and the email with my new ice date, I’ve been taking my uncertainty out on my packing—overthinking, over-buying, and just over-doing. Which shoes? Do I really need watercolor pencils and paper when I’m such a lousy artist? Are two sets of pajama bottoms enough for four and half months and if so, which ones? Striped but frayed or new but untested? For weeks I’ve been tripping over the beached whale that is my overstuffed navy-blue wheeled duffle that rests inert on my bedroom floor. My dog stares at it with surprising hostility for such a small animal. She hates it when I get a suitcase out and this one has been in her face for way too long. She’d climb into it if she could but it’s too tall. Poor girl. She’s not wrong to worry.

I’m definitely taking packing for four and a half months at the pole more seriously than my throw-my-favorite-things-in-a-bag-the-day-before style of packing I usually practice. I can’t just pop out and buy whatever I neglected to bring, nor can I have it mailed to me. (Well, I could, but it might take weeks or even months.) So I ponder and second-guess what I’ll want and need to enjoy a climate I’ve never experienced, to do my best at a job in a new kitchen, to enjoy leisure and festivities and socializing I can’t quite imagine.

At least I have the luxury of knowing that one crucial matter is (mostly) not my responsibility: staying warm. That’s right. It’s called Extreme Cold Weather (EWC) gear and it’s issued to every person who goes to Antarctica under the auspices of the USAP. (Returning participants/workers have the option to bring their own ECW so long as it meets certain specifications.) That means sub-contractors like me and NSF grantees who are doing the science the whole program is there to support will be stopping in Christchurch at the “CDC.” Because everyone undergoes pre-flight Covid testing, for the longest time I thought this was a foreign outpost of the actual Center for Disease Control. No. “CDC” stands for Clothing Distribution Center. It’s been weeks since I filled out a form detailing my height, weight, glove size, waist circumference and inseam. For the most part, these are not numbers I relish seeing in print and I will not be disclosing them here, other than my height, which, as a tall girl, I’m proud to report is six feet.

What will I be picking up, on loan for the duration of my stay, at the CDC? The first item occupies the most mental and physical space: “Big Red,” the massive, specially made, cherry-red Canada Goose parka that will keep a body cozy—or make it insufferably hot. Most people stationed at McMurdo in summer report they rarely use this monster; I suspect those living and working at the South Pole use theirs. The second item of note are the infamous military issue “bunny boots,” heavily insulated, “vapor locked” (they originally had a valve for non-pressurized military flights) and waterproof. These clunkers will keep the boniest feet warm in temperatures as low as -60° F. for five hours—or something like that. If you’re headed to Antarctica for an outdoor job bunny boots are critical; I wonder how much I’ll use them. The remaining items issued at the CDC are less exotic: bibs or snow pants, fleece jacket, beanie, gloves, neck gaiter, goggles and a balaclava. Everyone is required to wear their issued ECW gear on their ice flight, including bunny boots and big red. Makes sense, I suppose. It’s cold down there and I’ll be flying on a military transport plane without a lot of amenities. Depending on the type of military plane you’re in—they use C17 Globemasters and 757s which are also called C32s, not that these numbers and letters mean much to me—the flight between Christchurch and McMurdo takes five or seven hours and a whole lot longer if you boomerang.

I’m happy to know I’ll have all this ECW gear; it’s an insurance policy against my own arrogance in thinking I won’t be cold, a mistake I might make even though—or maybe because—I’ve spent my share of time in below zero temperatures. I grew up in the mountains—winters at 8,000 feet plus in Aspen, where I was born, were snowy and cold. Central Idaho, where I moved with my family when I was nine, was MUCH colder. I know it sounds like something you tell your kids when they whine about walking a block, but my sister and I really did walk a mile and half every morning to meet the Stanley school bus in sub-zero temperatures. (Back in Aspen we walked even further from our house at the end of Little Woody Creek to school on the mesa.) We did not have the equivalent of Big Red. It was the 1970s and we had cotton turtlenecks, OshKosh overalls, hand-knit hats, flimsy wool mittens that the snow stuck to in icy balls and what we called “snowmobile boots.” I remember being cold but what do kids care about the cold? I certainly didn’t. (I still don’t but how I loathe being hot!) As a competitive cross-country skier throughout high school I often raced 5 km, 7.5 km or even 10 km in sub-zero (F.) temperatures wearing nothing but long underwear and my super snappy canary yellow and sky blue Lycra racing suit. I also spent a full winter in Norway before heading for college, frequently skiing for hours on the très chilly Hardangervidda. The tip of my ear has been repeatedly frost-bitten—I remember the first time I pushed back my long hair only to come in contact with the oddity of the hard flesh that was supposed to be my left ear. It felt stiff enough to snap.

Cold as I’ve occasionally been, I’m in no way pretending any of this (admittedly fairly ancient) history compares to Antarctic cold. The average summer temperature at the South Pole is -18° F. This means that I’ll be wearing layers and layers of wool, fleece and polypropylene clothing when I go outside to walk, run or (maybe) ski. I’ll also be breathing through a balaclava (or two) that will, I hope, ease the harsh burn of that cold air hitting my tender lungs. I’ll let you know how it feels when I get there but no matter what I’m planning to spend as much time outdoors as I can. I mean, why else am I going? Sure, I’m looking forward to the whole experience—baking at the pole, meeting workers and scientists, seeing the glittering white landscape covered in ice and snow—but I want to get out there in it, to feel it, taste it, breathe it in.

In preparation for this extreme environment, I purchased several pairs of merino wool long underwear, socks and undershirts. (Purple and yellow shirts were on sale so that’s what I have. With Smartwool brand items running a hundred bucks a pop you could easily spend a minor fortune on these things.) I’m allowed 85 lbs. of gear, not including my ECW which weighs around 10 lbs. I’ll also be issued six sets of kitchen uniforms that weigh 10 lbs. or so but I’m given an extra allowance for them. In short, the rest of my gear—don’t we all love calling our stuff “gear” these days, as if somehow that Lululemon tank top qualifies as equipment, not an impulse buy. Anyway, the rest of my items consist of the regular things I’ll need to live and work in an indoor, heated environment with what I hope will be lengthy forays out into the cold—slippers, pajamas, sweatpants, leggings, jeans, sweaters, tank tops for under-uniform, non-slip work shoes, beanies, mittens (in case the issued mittens are too hot for my often hot hands), running shoes, underwear, many kinds of bras (sports, work, sleeping, leisure) plus a pair of really cool silver quilted down pants that I couldn’t resist because they were half off and a skirt, top and tights for dress-up on Christmas and New Year’s, both of which are supposedly celebrated with feasts and various polar antics. Oh, and a bathing suit. There’s a sauna at the pole! The remainder of my allotted weight will be taken up by all the toiletries a girl needs in a polar desert—humidity down there hovers around .03% which is basically zero as far as my skin is concerned. I’ll need loads of greasy moisture for hair and body. I have reptile skin in New York where the humidity runs around 75%; I can’t imagine what it’ll look and feel like in that sort of environment.

What else does a person like me pack when heading off solo to live and work for months and months?

One, my baking book that contains all my favorite recipes and a few essential baking tools that I can’t risk doing without (scale, favorite scraper, instant read thermometer, pastry bag and tips, etc.).

Two, my trusty MacBook since I need it to write and it’s the only way I’ll be able to communicate, via email, when the satellite passes over four hours each day. (McMurdo has Starlink but not the pole, thankfully.)

Three, books. Most of the novels, non-fiction and poetry I’m bringing are already downloaded on my Kindle but there are one or two tomes I’ll lug along just because I love the comfortable feel and look of printed books.

Four, luxuries. I’m bringing my own sheets because I’m a princess when it comes to percale and I’m cramming my own pillow into a stuff sack because who in the world would risk the hell of sleeping with the wrong pillow for months?

Five, sentiment and decoration. I’ve packed a slim book of family and dog photographs my daughter, Hattie, put together for me, a travel mug my son, Penn, gave me, and some photos of my favorite E.A. Wilson drawings that my husband, Dwight, had printed for me. The room I’ll be living in at the pole is, I think, 7 x 10—approximately the dimensions of a standard jail cell. I’ll put the prints on the wall along with photos of my family, friends, dog, and some New York scenes. Decorating the walls of your room, from what I’ve read, is essential to polar happiness.

I won’t be bringing any jewelry—just a single wedding band (actually, the one I’m bringing is my engagement ring) and my watch. I’m taking out all five of my earrings because wearing them would guarantee re-frozen ears. (Metal conducts the cold.) If the cold weren’t enough to convince me, strict kitchen protocol requires no ornaments—off with bracelets and necklace, too. I’ll feel a bit naked but that’s probably how I should feel given that the whole experience is going to be so new to me.

As I check off the final list of items—meds for three months, snacks and neck pillow for the plane, water bottle, last minute toiletries, shower shoes—I find myself dreading saying good-bye. I wish I didn’t have to. The toughest ones will be my kids and my dog. True, it will be extraordinarily difficult to say good-bye to my husband, Dwight. He’s the one I see every day and rely on; nobody knows me better. Still, he’s half looking forward to his own domestic adventure, home alone in our Harlem apartment, writing by day, eating his own favorite foods without feminine interference, listening to music late into the night. But my twelve-year-old dog will just be confused and mopey and my kids, well, it makes me tear up just thinking about not seeing them. Worse, I won’t really be within reach if they need anything. Of course, they have their own lives and are incredibly self-sufficient. I’d be deluding myself if I believed otherwise. Still, I’m pretty sure they know I’d drop everything if they needed me but that will be impossible when I’m thousands of miles away, in the great frozen south of the pole.

I’m breathless with excitement as Sunday approaches but I feel something else I can’t quite put my finger on. Maybe it’s just the longing for everyone I love that I’m sensing the opening edge of—or maybe it’s that damn novel of mine, still out there, looking for a home.

You’re poised, on the precipice! Bon voyage, my friend. Can’t wait to accompany you virtually!

Cree, I love this, and I'm so excited for you! PLEASE bring the colored pencils & sketchbook and don't second-guess yourself, just draw!