When I tell people I landed a kitchen job in Antarctica for the austral summer, 2023-2024 they either look at me wide-eyed and ask “Why?” as in “Why the hell would you do that?” or they light up and say, “Wow, that’s amazing!” and then pelt me with questions. I’ll try to answer as many of those questions as I can here, including the ones addressed by those who, as my son, Penn, put it, think I’m “a nut.”

Why Antarctica? I blame my father, Bruce LeFavour, who did some serious adventuring of his own, for handing me Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s classic, The Worst Journey in the World, when I was twelve. He told me it was the best book about Antarctica and he wasn’t wrong. The Oxford-educated Cherry-Garrard paid £1000 (about £120,000 today) to take part in Robert Falcon Scott’s deadly 1910-1913 Terra Nova expedition with the title of Assistant Zoologist, working under the great artist, naturalist and doctor, Edward Wilson. Cherry-Garrard’s book captures the warmth and camaraderie of the so-called Heroic Age explorers. He’s funny, human, self-deprecating and describes the cold and food and men with spirit and intelligence. After reading the book as a kid I sought out the other accounts of the various expeditions and their participants including those recounting the lives and mis/adventures of Ernest Shackleton, Roald Amundson, R.F. Scott, Tom Crean, Birdie Bowers, Edgar Evans, Frank Wild and Lawrence Oates.

I’m a massive re-reader; I can’t count how many times I’ve read The Worst Journey in the World. As a result, I’ve long had an imagined space in my mind that is life in Antarctica in the early 20th century which is why one day this past winter I set up an alert for postings in Antarctica on the job-seekers website Indeed. Why not? I’d trolled the cruises for the hell of it, none of which I could afford even if I’d wanted to go. But how I enjoyed imagining the lives and work of the firefighters, power plant technicians, construction superintendents, weather observers, construction coordinators and field coordinator FS & Ts—whatever they are. Just thinking about life on the ice made me happy. I’d open the emails and peruse the jobs, none of which I was remotely qualified for.

On May 31st I was lounging on our blue velvet sofa next to the dregs of my coffee, still in pajamas, mildly bored, done with the crossword, done with the Wordle, wasting my time as I waited for my novel to sell—or not. So like the monkey I am when I have free time and my phone in hand I clicked on my email—again. The only fresh email in my inbox was that Indeed alert so, since thinking about Antarctica never fails to distract me, I scrolled through the jobs. That’s when I came upon a listing for “Head Baker.” Huh, I thought. I can do that. I’ve done that. I like doing that. The little box practically begged to be clicked—APPLY NOW. So I did, just because it took all of three minutes, just because I had nothing better to do, just because I could dream and would so much rather do that than wait for an email from my agent.

Moments later, I read the automated email: “Hello Cree, Thank you for applying for the Lead Baker position, McMurdo Station with Gana-A’Yoo, Limited, Antarctia. Your application has been received.” And then I went on with my day which mostly consisted of reading, checking my email, walking, checking my email and not writing the other book, the one I have due. The following day I opened an email with the subject line: “GSC Antarctica Application Update.” I remember so clearly exactly where I was—on the subway platform at 96th street waiting for my local 1 train to take me and my groceries home to 146th Street and Broadway in New York City. I kind of figured it would say “We regret to inform you” or “Sorry but….” Instead it read: “Thank you for your interest in Gana-A’Yoo Service Corporation (GSC) Antarctica. This is to inform you that you have met the minimum requirements for the Lead Baker, McMurdo Station position.” To be clear, it was not that I had met the minimum requirements for the position that made me rethink the whole silly game of applying. I figured some bot had determined as much by scanning my resume. No, what changed my whole aspect in a flash was my reaction to the email. I could not stop smiling. I might even have done a little jig on the grubby platform—forgetting my novel, my groceries, my life in New York, my husband, my tiny dog—as the shimmer of possibility entered my mind: maybe, just maybe, I could go to Antarctica. How could it be? I’d applied on a whim, without giving any real thought to the questions when I checked the boxes for both winter and summer, for McMurdo and South Pole, glancing past the part that said the pay sucked and I’d be sharing a room, past the part that said the hours for all kitchen staff run to nine hour days, six days a week. Suddenly, standing there in the crowd grinning stupidly, the possible had opened up before me as a reality—of course I knew I probably wouldn’t get the job but at that moment I knew I had to try. I hadn’t been as happy as I felt that day for a long time—the idea of going to pole lit me right up. I don’t think I stopped smiling until I fell asleep—and maybe not even then.

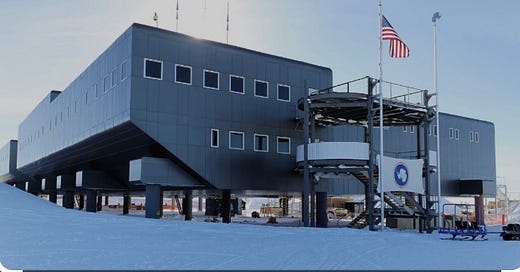

When I calmed down a bit the next day I could see that if offered a job I would need to pass a “Background & Drug Screen” and “Physical Qualification Process.” I’m healthy and don’t do drugs so I wasn’t particularly worried. Attached to the email I found my dream reading—the United States Antarctic Program Participant Guide. In it, I discovered that the United States runs three research stations in Antarctica plus several field camps. Palmer Station is furthest north while the The Amundson-Scott South Pole Station is, well, as far south as you can go or on the pole itself. The main, largest United States station is McMurdo Base which sits on the tip of Ross Island overlooking McMurdo Bay not far from Mt. Erebus, the continent’s active volcano.

Antarctica is a massive continent, somewhere around the size of the United States and Mexico combined or 5.4 million square miles. The ice surrounding the land melts to varying degrees during the austral summer when the sun shines 24-hours a day. These brief melts are the windows the early explorers either hit or missed (think both Scott and Shackleton whose ships froze into the ice forcing them to overwinter). These brief windows of ice melt also provide the opportunity to resupply McMurdo and by extension the other stations as all flights to the pole stop first at McMurdo. A single tanker, for example, arrives during summer to deliver the food supplies for the remainder of the year. (Except fresh food items or “freshies” that are flown, space permitting, during the summer months.) In winter, both McMurdo and the South Pole are populated by fifty or so hearty workers and a scattering of scientists who “over-winter.” In summer McMurdo balloons to as many as a thousand people while the South Pole station gains about one-hundred. The stations are run by the government for the purposes of scientific research which is conducted by grantees through the National Science Foundation. Gana-A’Yoo is a government sub-contractor in charge of “hospitality” services on the ice—food, janitorial, entertainment.

Nobody “owns” or has territorial claims on Antarctica. The Antarctic Treaty establishes the continent “for science and international cooperation.” With over fifty signees, the treaty, in force since 1961, emphasizes the use of the land and sea south of sixty degrees as a zone of peaceful scientific pursuit. The treaty also established essential principles of preservation: no exploiting, harvesting, or harming natural resources, sea life, birds or other forms of life. (There are no land mammals—if you’re thinking polar bears, go north.) Signatory nations also agree not to introduce any plant, animal, bacterial, fungal or sea life to the continent. All waste is (supposed to be) removed including human feces and urine. If you pee while taking a hike you do it in a bottle and bring it back to the staton.

I spent the greater part of June 1 reading the Participant Guide and dreaming of the strange, remote possibility that I might be able to go to Antarctica. The following day, June 2nd, I received my first email from a human being, this time inviting me to interview. Once again I spent the day floating on some strange form of unstoppable joy, unable to get the ridiculous smile off my face. I’d made it to the interview stage! Impossible.

It was time to tell my husband, Dwight. This thing was moving along quickly—far faster than I expected if I expected anything. I was a little nervous about telling Dwight that I might be leaving for as long as six months. It didn’t help that I already had a bit of a reputation for fucking off to wherever whenever I felt like it—just the previous year I’d spent a month walking in France solo, then there were the annual trips with my friend VZR to her place in Italy, more solo walking in France, another trip there with my friend LG pre-pandemic.

“Don’t get mad at me,” I began that evening. “I’m thinking of doing this thing.” He looked at me, at the giant grin I was failing to suppress. I’d piqued his curiosity although he appeared mystified by my dopey-dreamy-blissed-out expression. “What? Out with it” he said. I suspect he expects me to say something crazy but inconsequential like “I’ve decided to paint the hallway this really beautiful green.” Instead I say, “I might go to Antarctica as a baker. I applied for a job and got an interview. It’s far from a sure thing but it would mean being gone for six months.” Deep breath. It’s a lot to ask. I know that. But the truth is, I don’t think he had a chance against the expression on my face and to his credit he saw how happy I was and said “Wow, amazing”—or something like that. And then, I said, “Do you mind?” and he smiled and said, “No, do it!” I call that true love. He wants what makes me happy and enters into the adventure of it with me, sharing my enthusiasm. This is (part of) why we’re still together after more than thirty years. And then I told him everything I knew.

My interview was scheduled during my stay at Ucross, the artists’ retreat in Wyoming. I remember sitting in my beautiful studio looking at my practice answers to the standard screening questions. I had no idea what sort of person would be judging me via Zoom. I was pretty rusty—I could hardly remember the last time I’d had a job interview although I wouldn’t say I was nervous because what could I do other than be myself? Still, I was keyed up, excited, hyper-ready which pretty much feels like nerves. My friend RWR had advised me that every interview question is about your fitness and experience for the job at hand. So when I opened the screen and the sweet young woman asked me to tell her about myself I did it with an eye to baking: how I’d begun with gingerbread houses at Christmas and cookies when my parents went out to dinner as a pre-teen, how I ran my own bakery Pink Frosting and sold my goods at the Cold Spring, NY farmers’ market, how I worked as the baker at the Garrison Institute for several years and how it was there that I learned about working in a professional kitchen despite having grown up in the restaurant business. By the time the thirty minutes were up I felt I’d done okay and hoped for the email telling me that I’d made it to the next level. That email came two days later with an invite to interview with the head chef at McMurdo. He couldn’t have been nicer and two days or so later I had an offer letter even if it wasn’t exactly the one I wanted.

I was offered an “alternate position” as Head Baker from October through mid-February. (Four months, not six.) This meant, as the chef who’d interviewed me had explained, if offered a position as an alternate I’d be in line for a job if someone else either changed their mind or didn’t PQ or nPQ’d. To nPQ is to fail the physical exam requirements for work in Antarctica. He advised me to get the PQ process done as quickly as possible and if I did I might move from the alternate list to the actually-going-to-Antarctica list. Naturally, once I became an alternate I wanted the stats on how many alternates got called up but I’m a good girl and didn’t want to bug anyone so as soon as I was back in New York I started on the massive PQ packet.

The thing began with a massive PDF questionnaire covering every aspect of the applicant’s medical and dental history. I’m super healthy but I’ve had a few health issues in the past. I didn’t want to lie on the form—bad idea. So I wrote it all down, including an extensive cardio-pulmonary work-up I’d done just the previous winter for no reason at all, as it turned out. After an ultra-sound of my abdomen seeking evidence of gallstones, a complete physical, a pelvic exam, a dental exam with half a dozen x-rays, eye exam, bloodwork and a rectal exam (fun!) I faxed the form with the results along with evidence of my recent mammogram to the University of Texas Center for Polar Medical Operations. I think it was three weeks later that I heard back—I had not submitted the correct proof for various exams, each of which had to be signed by the physician along with their credentials, date, and address. I also needed a Covid booster and to fill out a questionnaire as a former smoker. Resubmit. Wait. The next communication, ten days later, requested proof that all that cardio-pulmonary testing I’d done was truly for nothing. In fact the doctor needed to sign off with a specific phrase: “I Support Cree LeFavour’s deployment to a remote polar region with limited medical resources.” As you might imagine, the very fancy specialist who wasn’t even treating me any longer had no desire to offer such a sweeping statement on my behalf. I tried anyway and did, eventually, convince her office to issue something close the statement. In the meantime, once I’d been turned down the first time, I sought out my very kind cardiologist at NYU who generally laughs at me when I show up because I’m so damn healthy. He kindly signed the letter and got it right back to me. I sent his letter, along with reams of test results, via fax, to the very particular doctors at University of Texas. Then I waited some more. Nobody goes to Antarctica as a worker who has not PQ’d or YPQ’d. I take comfort knowing that everyone, from Scott’s earliest expeditions onward, underwent a physical qualification process to determine fitness to endure the cold, isolation and limited medical resources at the pole.

As I was doing all of this boring doctoring, etc. I was still on the alternate list which meant I might well be doing it all for nothing. They pay, yes, but I spend the time and energy. (What did I care? We’re talking about Antarctica!) Besides, waiting to hear back from the docs in Texas or the admins who moved the employees around in Denver, determining who has a contract and who doesn’t, sure beat waiting to hear if any of the New York publishers my agent sent my novel out to wanted to publish it. By comparison, waiting to hear about my future in Antarctica was pure fun. Being the polite but determined person I am, on July 20th I wrote to my point person in Denver, a nice woman who graciously answered all my questions without seeming to mind a bit, to ask if the four bakers assigned to McMurdo with primary contracts had already PQ’d? Didn’t a single one of them have a troublesome boil or an bad tooth that might disqualify them just long enough for me to slide into position? I was essentially bemoaning my status as an alternate as gently as I knew how. She wrote back that alas, yes, they had all passed and being a baker was tough since there weren’t that many positions but if I was willing to do something else or go somewhere else I might have better luck. I immediately wrote back to say I’d do just about anything, anywhere, so long it was in Antarctica.

Two days later she emailed to ask if I had a minute for a quick Zoom. Staring into the computer a few hours later she handed me my dream. Would I consider, she asked, working as either a Steward or a Process Cook at the Amundson-Scott South Pole Station? “Fuck yes!” I said—but without the “fuck.” I definitely did say, “Yes, yes and yes!” and “Thank you!” I’d learned a bit more about McMurdo since the early, innocent days back in June and by the time this offer to go to the actual pole arrived I was feeling pretty excited about the prospect of going to the smaller, colder, more remote station. Not only would I have my own room—a big bummer at McMurdo is dorm or double-rooms—but I’d actually get to experience the extraordinarily extreme environment at 9,300 ft elevation. The warmest it’s ever been at the south pole is 7.5° F. Most of the time, even in “summer” which runs from October through mid-February, the temperature hovers around -20° F or even -30° F. The average year-round temperature is -56° F. I could not have been more excited. I’d done it! This time I really was in.

I yPQ’d about a week later. That’s when I started the shopping: long-underwear, wool and silk socks, down booties, a few extra beanies, down pants, four months worth of shampoo, toothpaste, and floss plus a giant duffle with wheels and most expensively of all new prescription wraparound sunglasses. Now I wait. I’ve shopped. I’ve submitted my travels documentation. My ticket cannot be issued, however, until I pass the extended background check the State Department now requires for deployment. It seems they are late, as usual, in completing the process, one that involves fingerprinting as well as a thorough history. I’ve been told they will get it done and to check my email. At least half the employees have yet to be cleared. I’m in good company.

I had another welcome, miraculous surprise the other day. The head of food services emailed to offer me a promotion to Sous Chef with the responsibility for breakfast and baking. How happy I am to be back to baking, where the whole adventure originated. I even got a raise. So that’s my Antarctic adventure thus far. My departure date could be anytime in the first two weeks of October. It’s Labor Day and I’m still waiting for an editor to fall in love with my novel—but because I’m also waiting to leave for the pole I can stand it, at least for now.

I’ve had like eighteen signs over the past few months that I’m supposed to go to Antarctica (also perused cruises and definitely cannot afford that -- my plan is to try for an artist grant). I’m completely obsessed, cannot stop thinking about it. I have no idea when I followed you on Instagram but tonight this post showed up when I opened it and it feels like another sign. I’m so excited for how far you’ve gotten with this and can’t wait to follow along on your adventure!!

When I heard you were going my immediate reaction was "wow, how fucking cool!!!" combined with the teeniest pang of jealousy. (I'd never pass the PQ...) I'm sorry I couldn't make the party tonight -- I'm on a flight home from Sydney right now -- but I'm thrilled you're doing this substack. Good luck and stay warm!