After three months at the Pole, McMurdo feels entirely different. I’m not a timid freshman anymore. No, in some ways, by going to the Pole, I’ve jumped the line in terms of experience. I might even go so far as to say I feel a little glamorous as “the baker” returning from the Pole. Many people in the United States Antarctic Program (USAP) never go to the Pole and, if going to Antarctica is cool, going to the South Pole trumps it. It helps, as I survey the rugged Kiwi construction workers in their bright orange t-shirts, bearded heads bent over piles of mushy, flavorless food, that I’ve been there and back: I’m happy with the job I did, not nervously wondering if my cakes will fall when I bake them at 10,000 plus feet above sea level. The room hasn’t changed—the chick with blond dreads piled high is still here as are the massive Irishmen with their long red beards, the precise image of the good huntsmen, fresh out of Grimm’s Fairy Tales. The military types crowd into the tables near the soft-serve machine, distinguished as much by their neat grooming as by their head to toe camo.

The galley hasn’t gotten any prettier—it’s as bleak as the average high school cafeteria. There’s no ramen to be had here but McMurdo does sport a panini press and ample Carter administration cold cuts (maybe this far north they date from Bush 2? Who knows!). I put them to work, however dubious, on a ham and cheese sandwich.

The next day, I walk to Hut Point to marvel at the beauty. Summer has left its mark. The hillside is rocky not snowy as are the streets of the ugly little “town.” As I move away from the disaster of the station itself, I realize how quickly I’d forgotten just how goddamn outrageously gorgeous the mountains and ocean are—the distant deep blues against the snowy white, the geometry-perfect squares of sea ice floating in the bay, the spilled vanilla milkshake shape of the massive glaciers flowing out from between mountains, the stark black volcanic rock against white. And then there are the penguins.

I come over the rise and there sit on the spit of land that is Hut Point—penguins in an unflappable cluster nestled just up from the ice, resting quietly on the snow, doing pretty much nothing at all. I stand quietly, awed. They don’t even bother to look my way. Below, down on the ice by the sea, a single, apparently youthful bird, paces back and forth in distress, lacking the brainpower to find his or her way back to the group on the hillside. I stand out of the way, observing, resisting the desire to ever so gently herd it toward a break in the cornice where it could easily return to its group. I’m rapt, the bird’s clumsy movements the greater part of its toddler charm as it stumbles, totters and hops. My hand freezes as I hold my camera for ten minutes at a time—even in the balmy 15°F air. I observe a large (leopard?) seal swimming back and forth, lustily eying the penguin. This is when I remind myself that picking up the penguin and carrying it back to its group would violate the Antarctic Treaty.

I’m housed in a room with a girl (forgive me, it’s the eager optimism and apple cheeks) who arrived the same day I did but she’s wintering-over and I’m about to leave. This is her first time on the ice. I can’t believe anyone would sign up to winter here without sampling the summer first. I try to sound encouraging but I think she’s entirely nuts.

In the afternoon I do what I can to arrange a tour of the interior of Scott’s Discovery Hut. No luck. Maybe, on some level, it’s the one thing I’m leaving undone so I have an excuse to come back? I return the ski boots I checked out for the season and the guy in charge of rec hands me my forty bucks back. The bills seem like fancy paper, alien, like I’ve forgotten all the fun things they can deliver; I haven’t carried a wallet or credit card for four months so I shove them in my pocket. (I’ll find them the next time I go skiing, no doubt.)

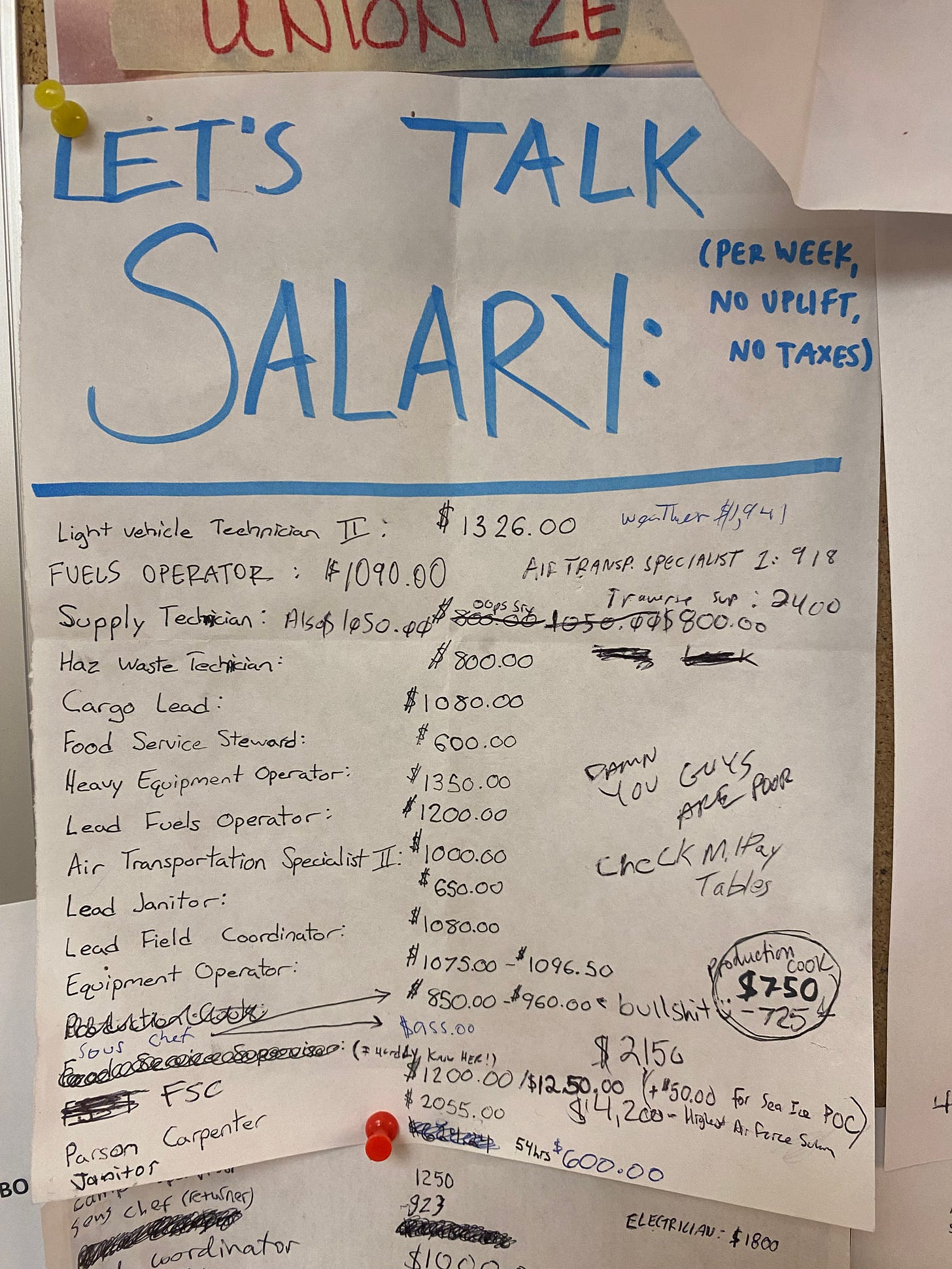

In my reverie of popping in and out of the galley to drink cocoa, read and just be a free person, I make the mistake of running into my über boss. He’s a nice guy but of course he wants to do my end-of-season assessment and, of all things, asks me to “put in a few hours in the kitchen.” For fucks sake, I think. But rather than saying it, I joke with him about how crazy he is to ask it of me while agreeing to log two hours back with my friendly former boss in the Freshie department. I make 20 dozen hard-boiled eggs and cut a bunch of cheese cubes for brunch service. Grrrrrrr. (This sign on the bulletin board in the corridor says it all.) This place is definitely all work and no pay.

The rest of the Polies arrive that evening. (I gained very little other than a tiny moral victory, it turns out, by departing early.) The two housing with me and the freshman are ready to drink and party, their stowed bottles of Bacardi and Kahlua at the ready. I’m just trying to stay awake during normal “daylight” hours. Happily, I run into the carpenter friend I did an epic 12-mile hike with when she visited the Pole over New Year’s. She’s terrific company—we never run out of things to talk about and she keeps the ideal pace. Exhausted as she is from closing down a field camp, she offers to get up at 5:30 AM the following morning, the day of my departure, to do the Castle Rock hike. I’m incredibly grateful. (Doing the trail solo isn’t allowed.)

The hike, next to our adventure at the Pole, is among the most memorable and pleasurable things I do the entire four months in Antarctica. I think I might have suffered the endless hours of kitchen work all season just for the views and for the feeling of being on the glacier, walking where I imagine maybe Cherry-Garrard once walked. (Why not? It’s possible.) With Mt. Erebus shrouded in cloud to the fore and the shocking blue sea ice and mountains behind, I’d give a great deal to walk it again. I can’t think of a better way to spend my final morning in Antarctica

Back at McMurdo by noon, I load into the massive machine that is the “bus,” ready for my flight back to civilization. Naturally, because everything USAP does makes sense, the group of sixty or so arrive at the airfield a good two and a half hours ahead of time. I’m not one to sit on the bus, no matter what kind, when it’s my last chance to stand out on the sea ice of McMurdo Sound, marveling at the light and surrounding mountains. Still, I’m cold by the time the ever-impressive C-17 lands, unloads, re-loads. I suppose it’s a fitting goodbye to the coldest continent.

And then I’m in the air, a little sick at the thought that I might never return, but elated to be moving on with my life. Five hours later the wheels bounce over the tarmac and when the door opens I’m surprised to step out into the dark. Then again, it’s almost 10 PM. Soon, I’m pushing a luggage trolley through customs and then to the Clothing Distribution Center to return Big Read, bunny boots and all the rest. The air smells of plant matter and exhaust. I feel the heat and humidity but, honestly, it impresses me less than I expect. I suppose after a full winter on the ice I’d be floored.

After dumping my bags at the hotel I head out. It’s late on a Friday but I’m not giving up on a meal and a glass of wine. Christchurch at midnight throbs with rowdy youth, the women tottering on impossibly high heels and teeny-tiny skirts, the men looking schlubby by their sides in their logo t-shirts, jeans and white sneakers. The city sounds and feels alien and I wander, unable to find somewhere I plausibly belong. Finally, a Korean BBQ joint with plenty of open tables that closes at 3 AM, beckons. Inside, I find two of my fellow Polies. I join them for a celebratory glass of wine and a hefty dose of Pole gossip before heading to a quiet corner where I eat a pile of raw salmon. It’s spectacular!

I have two days in Christchurch to unwind. The dark isn’t as enveloping and wonderful as I’d made it out to be at the Pole, back when I missed it. Rather, I find it getting in the way of my plans: hiking, running, making my way to the beach. I indulge my abused feet in a pedicure and glam myself up with my standard navy blue polish manicure. I buy new pants, a shirt and a pair of sandals. I drink an inordinate number of flat whites which never stop pleasing me. I try to erase the entire taste memory of coffee at the Pole. I think it’s working. The internet does all the magical things it’s supposed to do 24-hours a day.

I wander the Botanical Gardens, buy myself a steak and a glass of decent wine to go with it, take long showers and, on the night before I fly out, have dinner with an old boyfriend. We haven’t seen each other in thirty years but it doesn’t seem to matter. I find only warmth, intelligence, humor, self-awareness, curiosity—all the qualities that drew me to him in the first place. It’s a reminder to trust my past self.

It’s also a surprisingly strong finish to my trip, leaving me with a sharp hunger for more—depth of conversation, memories in common, inside jokes, a shared meal. it’s time to go home. Soon I’m off, bags checked, moving toward the NYC finish line, Kindle loaded for my 24-hour plus journey from Auckland to Houston to Newark. I’m almost home.

.

Amazing! (And I smiled when I saw that you’ve got to go on one final giant walk — that’s my Cree!) Now come home safely, where the coffee is always good and where we have missed you dearly!

aah, the salience of penguins, whose brains are still programmed for flight, millions of years after they stopped flying, giving them that distinct waddle, wing propulsion supporting underwater diving. there they are on the ice, totally self-contained.