It’s officially Thanksgiving in the New York City but not here. At the South Pole we put out the big meal in two seatings on Saturday. Like Christmas, it’s a station-wide holiday—unless you work in the galley as either a cook or steward. All I can think about are the six pumpkin pies, six sweet potato pies, six apple pies and four flourless chocolate cakes I’m baking plus the rolls and chocolate covered dates for one-hundred thirty people.

Three weeks in to my time here, the kitchen at last hums along with its full allotment of working bodies—head chef, three sous chefs and a production cook. My boss half-ironically calls us all “Chef.” I mostly call him “Boss” and he often calls me “Boss” back or, sometimes, “Dusty,” when I’m covered with flour. I’m usually covered with flour or confectioner’s sugar. (Same look.) It’s been tough getting to where we are now, fully staffed and figuring out our schedules, cleaning the kitchen, sorting and organizing the ingredients. All the credit goes to my hyper-energetic, extraordinarily hard-working boss who’s also a genius of logistics—not to mention all his other outstanding qualities that make him a pleasure to work for. (And no, I very much doubt he’s reading this so I’m not just sucking up.)

For the first two weeks I worked from 2 AM to 2 PM or even later. (Below is the 2 AM sky from the galley.) The days were grueling although I got to know the older guys who arrive at the start of 6 AM breakfast. They liked my strong coffee and the Denver Scramble I invented to mask the boxed, frozen, blended eggs that are no substitute for the real thing. I began with this schedule because that’s the schedule the previous baker kept. But my boss has remade the kitchen and, with very few exceptions, everyone who spent the winter on the station is now gone. It’s his kitchen now.

The first week on station was the hardest. It was just me and my new boss who arrived on the second flight, post-winter-over isolation, which meant the chef was still around and the stewards. (The baker managed to escape on a Basler three days after I arrived.) Working twelve hours at a stretch with an N-95 masks suffocating me added to my woes: baking in an oven that I couldn’t control, unfamiliar ingredients and, most of all, at an effective altitude of 11,000 feet. The altitude makes sugar liquify at low temps, cakes and bread rise far too rapidly and then, if they don’t have the structure to support them, fall. On top of that the flour couldn’t be drier (or the air for that matter) which means liquids have to be increased and whatever emerges from the oven dries out rapidly. Oh, and I pulled a muscle in my back which then went into spasms.

My proudest moment was when the Physician’s Assistant and Doc I went to see for some meds were nice to me and I burst into tears right there on the examining table. I hate having my emotions that close to the surface but it happens. With not-fun meds and foot warmers attached to my shirt to relax the muscles, I kept working and the Baslers kept right on being canceled—Covid, priority flights to field camps, mechanical issues, a measles scare at McMurdo and always, the weather.

Great as these little World War II workhorses are, the visibility and temperature limits for the tiny, ancient plane are strictly enforced. Three big TV screens in the galley show the flight status and roster of passenger coming and going on each flight. On the morning of the scheduled flight an announcement sounds over the loudspeaker and on radios throughout the station: “Flight ZSP004R (for example) activated. Estimated arrival South Pole 1300 hours” or—more often—“Flight ZSP004R cancelled.” I watched again and again as those hoping to escape the Pole listened, holding their breath, only to crumple each time their flight was scrubbed. I didn’t care who left but figured things had to get easier when the new chefs arrived.

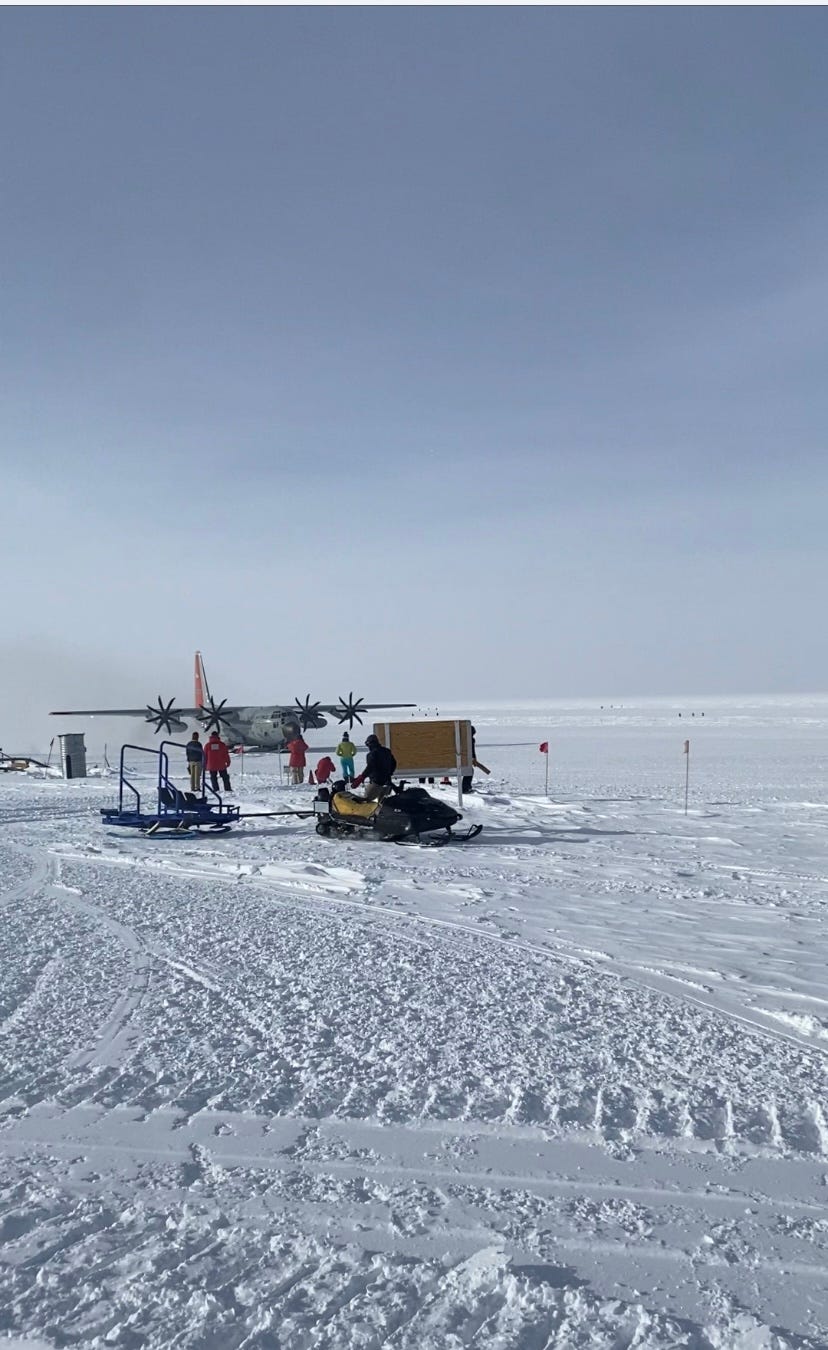

Finally, it was no longer the Basler but the comparatively large C-130 that rescued the final stragglers and brought in the rest of the kitchen crew. The Basler can carry in a dozen or so bodies and their first priority bags to the Pole but can’t take-off with that kind of load in the thin air at the Pole. At most, four people hitch back to McMurdo when a Basler returns; the C-130 can deliver and carry back thirty or forty!The arrival of the first C-130 of the season made for a big event—I ran out, just off my shift, to catch a glimpse of the military plane landing on its skis and to experience the excitement of those arriving. Actually, I stood there for ten minutes or more in my thin pink Lulu shirt, open chefs jacket, chef pants and rubber clogs. People bundled up in Big Reds, snow pants, bunny boots and face masks stared and commented—“Aren’t you cold?” Forty below zero isn’t nothing but weirdly, I wasn’t. Besides, who doesn’t love being called ”Badass,” especially by military dudes in heavy army issue jackets

.

The plane delivered our third sous chef—the production cook followed on the next C-130 along with the first fresh eggs and fresh fruit I’ve seen in weeks. (They sent eggs, a few apples and tangerines, onions and cabbage. Honestly, the choice of items strikes me as more of a prank than a considered delivery.) The mask-wearing new arrivals create an oddly visible hierarchy of new verses established residents. For five days those wearing masks are both ostracized (they have to eat in their rooms) and marked as newbies. I pity all the new masked people because I know how much I hated it. Oddly, I find myself in the odd position of knowing more than the new arrivals—the best exit to take for a walk to the ceremonial or geographic pole (Zulu) or where the packets of ramen can be found

By the time the whole kitchen staff has assemnled it becomes clear I should be working the night shift. There’s only one oven and everyone needs it at the same time, not to mention the work surfaces. Kitchen real estate is counter space and speed rack slots. As a baker with trays and trays to fill and bake, speed racks to move from work space to oven and mixers to monitor, I want all I can get. To shift to my new, almost opposite schedule, I take Saturday off and then half of Sunday. My new shift runs from 6 PM to 4 AM if I take the hour break I’m allowed—or 3 AM if I skip it. My goal is to work the allotted nine hours I’m contracted to work not the twelve or thirteen I’ve been working. There’s no over-time at USAP.

With those days off before I began my new schedule I finally find time to sit with cocoa in the galley, reading and writing. Charley Taylor’s gorgeous piece on my husband Dwight’s new book, The Upstairs Delicatessen, arrives in my inbox. I love Charley’s writing—always unflinchingly rigorous but with his defining warmth and generosity at center. His memories of visiting our house in Garrison, NY throw me into nostalgia for the days when my kids’ tiny bodies, stuffed in footy pajamas, could pile on a sofa bed with two adults and an overweight Lab.

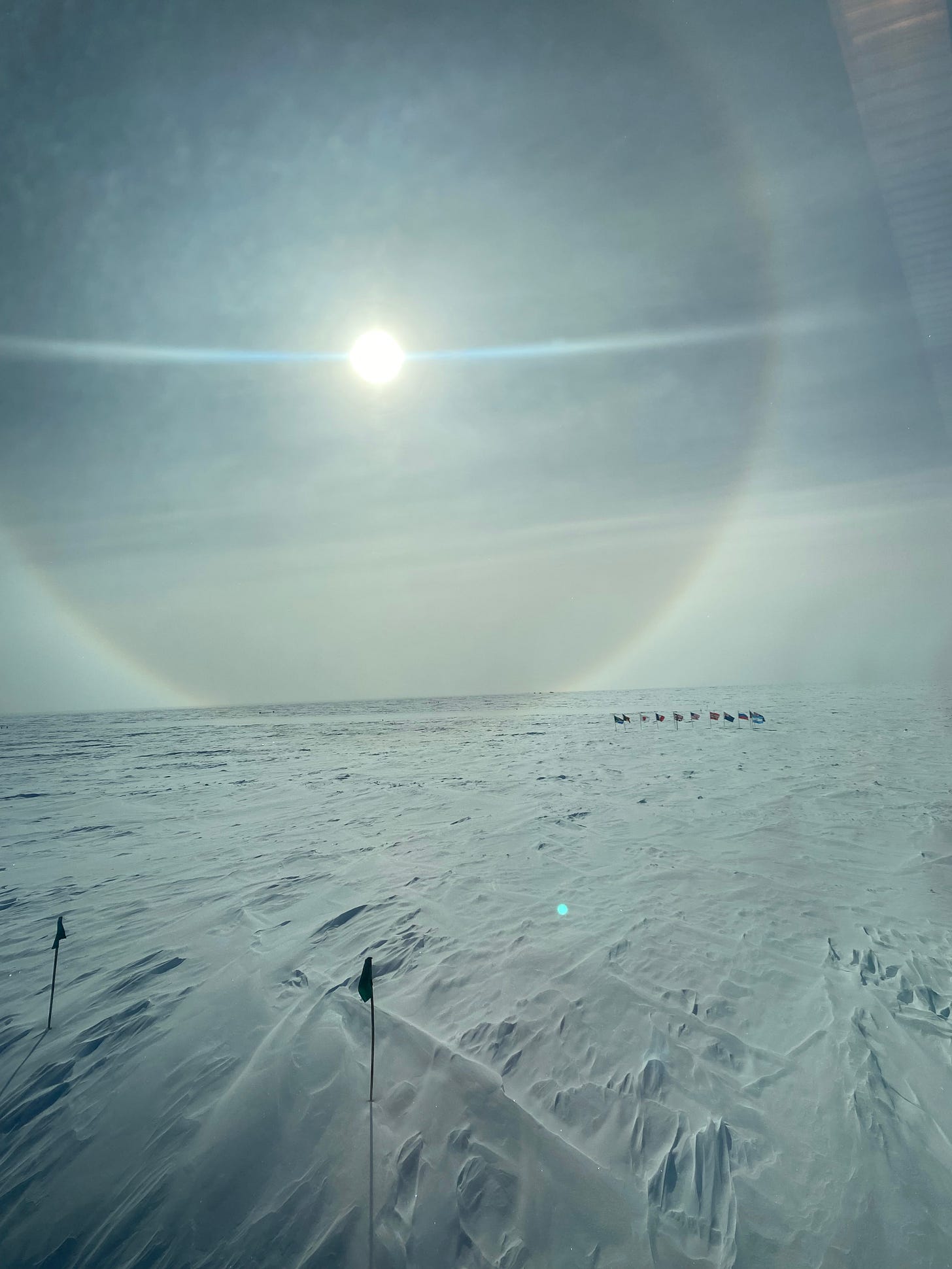

Later, over dinner of ramen with frozen vegetables, I read another chapter in Mariana Gosnell’s wonderfully technical book on ice titled, naturally, Ice: The Nature, the History, and the Uses of an Astonishing Substance. Gosnell offers a fascinating education for me as I live atop two miles of compacted H2O. I’ve not reached the section where, presumably, she will discuss compacted ice at extreme low temperatures, but her opening chapter on how a pond freezes has me rapt. From her little cabin she observes pond water steaming on a day when the air drops to 5° F. And then she describes what I see every time I step outside into the-greatest-freezer-in-the-world on the back dock— “mica-like glints” in the air falling from seemingly nowhere on the sunniest possible day

.

Quoting Paul A Siple’s 90° South: The Story of the American South Pole Conquest, she notes these crystals are “like dust beams in the attic when the sun pours through small peepholes.” The other day, when I put two full sheet pans of coconut brownies out to cool, I stared up at the clear blue sky as these glints of crystalized air fell on the surface of the hot black cake. Although they are by definition moisture, they are so miniscule as to be inconsequential—tiny bits of atmospheric moisture entirely unlike the heart-attack inducing, wet, heavy flakes of snow that fall during a Nor’easter when the temperature hovers around 31° F.

I read for a little longer and then head for bed. I try to stay up late to acclimate to my new schedule. Sunday morning, I sit at a table in the big cafeteria watching my fellow Pole occupants march through the brunch line. How refreshing to feel like myself two days in a row—to wear my own clothes and let my long hair fall loose. I’m painfully weary of my dehumanizing black chef’s uniform, hair tucked up severely in a bun and even of my head scarves, improvement that they are over the ugly, issued cap I was required to wear in McMurdo. Wearing clothes that have been with me in my other life—clothes I chose back home, jeans my dog, Maebelle, napped on countess times or a t-shirt I’ve been backpacking in—makes me feel more like myself just as writing and reading and walking have returned me to center, grounding me in my decision to be here. I’ve been spinning through cycles of work and sleep with nothing in between. Such a life goes down hard, wearing out body and mind. It’s been a long time since I recognized the extraordinary privilege of having critical blocks of time to read and write.

Sunday afternoon I take a longer walk—although not to the horizon—and it’s grand pleasure especially since it’s only twenty-two below zero. The air feels positively balmy, I swear, warm enough not to cover my face. What a joy to explore this crazy compound at the tip of the earth so far from anywhere. As compact as the station itself is, with its surprisingly elegant gun-metal gray exterior and tall shiny metal silo at one end, the station has its share of sprawl, although nothing like McMurdo’s. There are fuel tanks and various outbuildings plus bulldozers and snowmobiles and vans with skis instead of wheels. One of these sheds contains the skis I need to get my hands on

.

The tall metal thing is called, most appropriately, “the beer can.” At the top is where I throw my garbage after mopping. The stairs from the bins lead down to the food storage area where the temperature, something like six floors beneath the station in the ice, hovers around -70° F. Those half a dozen turkeys for Thanksgiving and the steaks that were served yesterday night and the flour and the eggs in cartons that I bake with (50 grams per egg) all come from this cavernous space.

Once a week my boss orders what we need for the coming week. Those working in supply bring it up from the bowels—a cold job for sure—and then we unload it into the walk-in or onto the metal grate of the best-freezer-in-the world. I add items from my list—chocolate chips, confectioner’s sugar, AP flour, oats, frozen peaches and blueberries. The usual, really, but all of it has been frozen, sometimes since the Obama administration. (Well, not quite, but I like to say it anyway.)

Back in New York I have a reputation (mostly with my kids Penn and Hattie) for consuming items that are well past their due date. In fairness to me I only do this with “live” foods such as yogurt, cheese, kombucha. You know, old stuff that’s just fermenting. Well, here everything has long since passed its due date—sometimes by as much as five years. Then again, molecules stop moving around and food slows its inevitable process of breaking down at seventy below. To a certain extent, right? Unfortunately, over time the food gets contaminated by other items—most notably the jet fuel that runs this place. My flour and the outer two inches of most of the ice cream offers up a faint hint of gasoline I fear I will forever associate with the Pole. My solution: don’t eat the ice cream and bake with lots of spices whenever possible. There will be no sugar cookies or angel food cakes emerging from my oven.

As I did at McMurdo, I set up what amounts to an office in the galley to write and work on my menus for the next two weeks. First is the breakfast item. When I arrived, oh so fresh faced, I assumed I’d be making everything from scratch. What else would I possibly do? I’m supposed to be baking, after all. The reality is more complicated. There aren’t enough ingredients on station—butter, flour, fruit, nuts—to make everything from scratch even if I had the time—which I don’t. I have to use the items the galley has on hand some of which are pre-made, four-years-frozen muffin mixes (just add water), pre-made croissants, turnovers, and Danishes plus doughs for cinnamon rolls that proof overnight. I’m coming to terms with this although I’m holding the line on lunch sweets, dinner dessert and (mostly) bread. (The frozen, pre-made baguettes aren’t half bad.) Sometimes people say, “Oh, you’re the baker! I loved those cherry turnovers this morning. Wow!” and rather than saying, “Those crappy things?” I’m learning the kindness of saying, “Great. Happy you enjoyed them.”

The new mid-rat schedule (midnight ration in Navy speak) schedule seems to be working. After nearly a week I’m sleep deprived for sure, but I can also focus on doing my job without other bodies in the way. Here, Thanksgiving is tomorrow—I’m ready but tonight’s 6 PM to 3 AM will likely be closer, as was last night’s, to 6 PM to 5 AM. Right now, it’s closing in on 5 PM. I need to transition into work mode, put on my uniform, tie back my hair, cover my head with a scarf or hat. Become that baker in the night kitchen. But I pause, staring out the window on the blowing snow, very much missing my family who are probably stuffed from their Thanksgiving turkey, potatoes and pie way back in New York City. Today, I’d like to be home with them.

Cree: I know Cole pretty well; especially from her days in politics and activism. You two have to be the toughest, most resilient pair of sibs I have ever encountered. Persevere!

Fascinating glimpse into your life!