I’m suited up in big red, snow bibs and bunny boots (the latter swapped for a smaller size at the kind urging of a co-worker after my flipper feet trip me up in the dressing room and I fall like a tree in front of everyone). I’m hot, but so is everyone else. I remove my coat and wad it under my arm where it feels bulky as a kid’s sleeping bag. The group passes through a perfunctory passport check and my bags ace the weigh-in with three pounds to spare. Fruit in pockets doesn’t count—it’s part of my “body weight” with carry on—computer, Kindle, book.

In no time we’re transported by bus to a giant green C-17 that looks like any other military plane to my uneducated eyes. Actually, it looks like a toy since I’ve seen plenty of models but never the real thing close up. Before I know it, I’m inside the big-bellied beast, its end wide open while the military crew, members of the New York’s Air National Guard, load massive pallets of cargo. I’m in the last of the eighteen net seats that run back-to-back down the center of the plane; there are another twenty or so running down each side of the plane plus two five-by-five blocks of recognizable commercial airline seats at the center, back and front. The mostly unadorned metal interior curves above me. Punctuating the functional space is an outsize American flag hanging vertically at the front of the plane. This is America.

We’ve been warned about the engine noise. Half the group sport padded over the ear earphones, the kind the cool kids wear on the NYC subway. The rugged dudes (mostly) wear them perched on their beanies, at the ready. I’ve brought this kind of bulky earphones along, too, even going so far as to emulate the pros by placing them at an angle across my beanie. Because I’m one of those ninnies who fears deafness, plugging my ears with my fingers when express subways, ambulances and firetrucks scream past me, I’ve added the protection of silicone earplugs to muffle the sound.

We taxi for what feels like a mile but since there are no windows it’s just noise and the lurching, occasionally bumpy movement you feel moving down a runway in any plane. Then the motion stops and the roar-whine-whirr of the powerful engine grows louder. As the noise increases so does the palpable tension of propulsion withheld—energy in check—until with a roar all the energy releases as the plane shoots off down the runway—I can’t see the speed but I can feel the G-force push me sideways. A thud and then nothing as the light, vaguely sickening lurch hits me in the belly signaling wheels up. Behind my glasses I’m teary at the stunning reality of being on this plane, in the air, at this moment, heading to Antarctica.

As the plane ascends steeply, I yearn to see out but there are only four round windows in the body of the plane, two on each side, fore and aft. I’d imagined staring down at the black, white-capped water swirling below, the sea Shackleton and five of his men crossed in the James Caird, a 23-foot lifeboat. The now legendary journey from Elephant Island to South Georgia, the only inhabited place in the Southern Ocean, consists of 800 miles of open ocean and when I say “open” I mean open.

The Southern Ocean, defined as the uninterrupted band of water south of the 60th parallel, isn’t only reputed to be “the stormiest in the world” as Cherry puts it, it is in fact the most turbulent, coldest, windiest part of the globe—below and above water. The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC)—like the Gulf Stream, it’s important enough to have a name—is fueled by the famous southern winds. Seamen and explorers have long referred to the “the roaring forties, furious fifties, and screaming sixties”—the source of the phrase eludes me, but Shackleton certainly knew it and invoked it. These winds not only drive the ACC (which happens to carry more than 100 times the flow of all the rivers on earth!) but create massive waves as a result of vast interrupted fetches (the distance of open water). This is about as far as my grasp of the matter extends but I have read, as has any fan of Antarctic literature, of the many difficult passages through these rough seas.

The moment we’re free to move around, I leap up and head for the window. Alas, all I see are plain, shapeless clouds that could be hanging in the air anywhere on earth. The most interesting thing they’re doing is obscuring my view. Back in my seat, I paw at the brown bag lunch someone handed me before boarding. Munching half of an unidentifiable sandwich I’m too awed to read for at least an hour—all I can do is think about is the great white south, Antarctica.

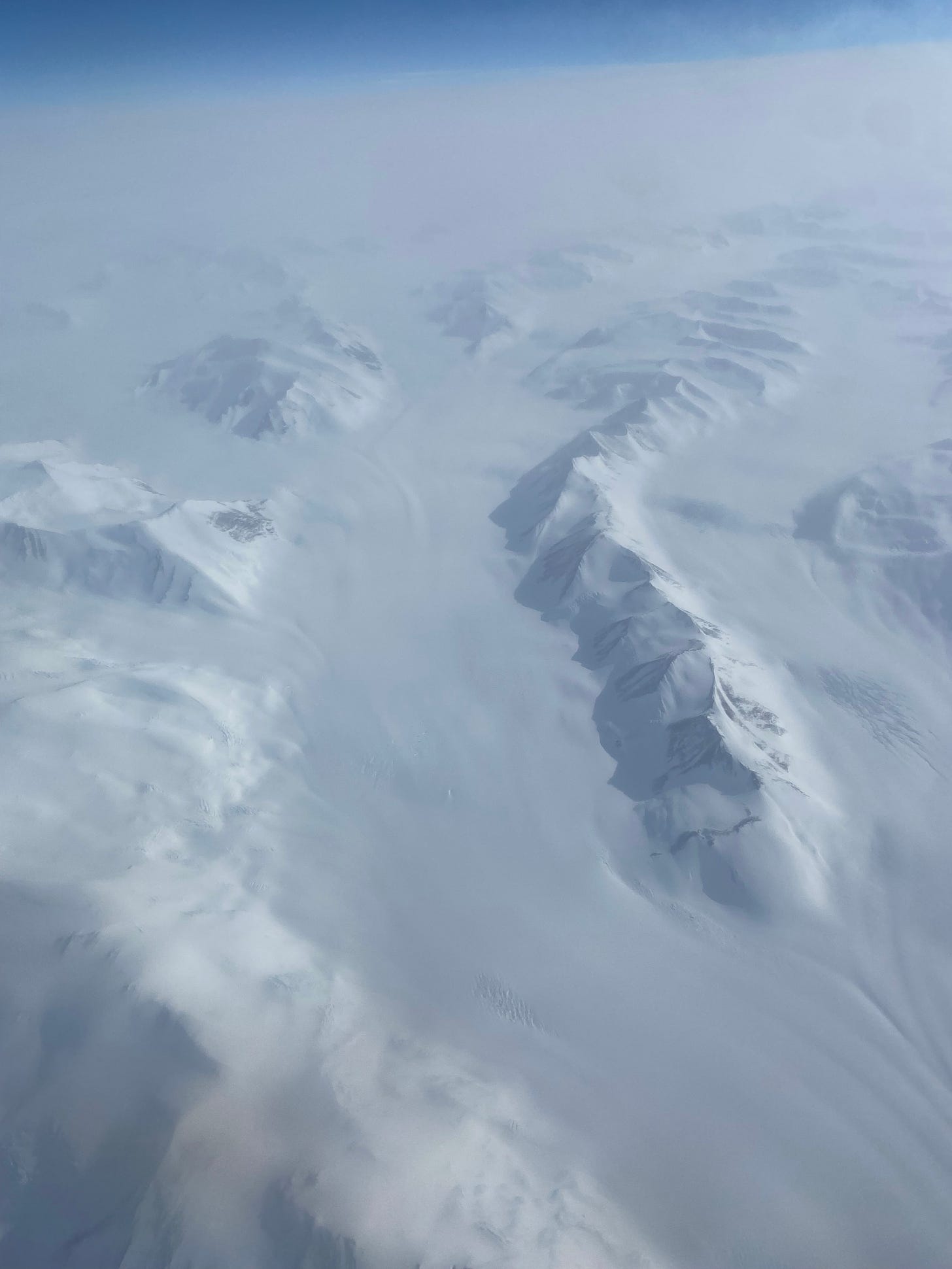

The flight lasts nearly five hours. I read Peter Matthiessen until I notice someone gesturing to a friend to look out the window. The space around soon grows crowded as an orderly line for the window forms. When my turn comes, I step up, sticking my face against the imperfect glass. There, spread out beneath me, is the most magical sight: the Transantarctic Mountains, as white and pure and perfect as can be. The unblemished peaks seem to float in the clouds as if the valley bottoms between them are filled with the densest, whitest fog. But it’s not fog—it’s ice. Miles and miles of ice that has built up over 34 million years and is as much as three miles deep in some parts of the continent. (In the interior of the continent the ice never melts—or melts very little. Some geothermal heat from the earth’s core evidently melts some of the ice shelf from below and this water then flows into lakes.)

I step aside and let someone else have a look. I stand there, looking out the window, for the rest of the flight, ceding space to anyone who wishes to take a turn. Eventually, the whole planeload of people seem to grow bored of looking so I have the window to myself. That’s when things start to get incredible—or should I say even more incredible. Unfolding beneath me I see the pack—the famous chunks of ice that move and flow and, depending on the weather, lock together into a solid sheet. Scott’s first expedition was trapped in the pack ice. Shackleton, of course, most famously found himself caught in the pack with no way out. His boat, unlike others forced to over-winter, was crushed by the ice and eventually sank on November 21, 1915. From the air I can see the channels like those Antarctic sailors attempted to follow—open water, almost like rivers through the ice where the cobalt blue lines snakes between the floating ice sheets.

Beyond the pack lies land—or is it more ice, a giant berg, perhaps? It’s hard for me tell what I’m looking at. What appears to be a glacier pouring into the sea forms a vast white cone, broadening as it approaches the water. (Could this be an ice tongue, like the one that extends from Mt. Erebus? I just don’t know…are there smaller ice tongues? I’ll have to ask a glaciologist if I meet one, which I just might.)

I cannot get enough of this strangely geometrical view consisting of variations on blue and white in every possible shape, but I know I must peel myself away from the sight when the announcement to buckle up comes over the speaker. I inhale one final dose of the astonishing view, the most singular if not the most beautiful I’ve ever set eyes on.

It’s disconcerting landing when you can’t see out the window and therefore can’t know when that jolt of wheels touching ground will occur. Actually, we’re not literally landing on the ground; we’re landing sea ice with compacted snow on top to make what’s called Phoenix Runway. I wait for the grind of being back on earth—it seems to take forever—and then it’s done and surprisingly smooth and easy. Before I know it I’m stepping out into the bright sun of the Antarctic spring, the snow and ice reflecting light from every direction. En masse we march toward waiting vehicles. There are vans—plain old airport shuttle sorts of vans emblazoned with the USAP logo—but to the left a red monster of a machine idles, waiting for passenger. I have to ride in it and I do. No, it’s not the famous Ivan the Terra Bus, a beloved and rather ancient transportation bus. This is the newer version of Ivan and it’s a ladder climb into the cab where six or eight of us sit open-mouthed, grinning at our good fortune to be where we are at last.

It's thirteen miles from Phoenix Airfield to McMurdo Station but I’m so enraptured by the ice and the violent white light that it feels like five. We pass Scott Base, the moss green buildings that make-up the modest home of New Zealand’s Antarctic base. Up a steep hill, past Scott Base, three massive circular fuel oil tanks mark the outskirts of McMurdo. The massive machine crests the hill and there it is—McMurdo Station or should I say town? McMurdo is a complex of interconnecting roads, strange sheds, metal dorms, warehouses, bars, workshops, fuel tanks, trucks, tractors, snowmobiles, garages and loads of various dumpsters for recycling and trash. Visually, it’s a very busy place.

After a brief welcome lecture about sexual harassment and how lucky we are (as if we have to be reminded) we line up get our room assignments, keys and computer cards. I’m early in to get help setting up my internet access which comes through the USAP government server. My new email has a .gov address. Weird! Before I can sort out access the whole system crashes and by the time I make my way to my room it’s late in the game. One of my roommates and I arrive at the same time—she takes the bed by the door and I take the bottom of the bunk bed. (She deserves the better bed since I’m about to leave for the Pole.)

For a minute I can’t quite believe I’m sleeping in a bunk bed. It feels confined and childish and just wrong. Oh well, I think. I can do anything for two weeks. I’m shown the kitchen in a quick galley assembly—everyone is due at work the next morning. I’m told by the very nice uber-supervisor who agreed to get me down to McMurdo early, that I will be working what are called “town hours.” Town hours are 7:30 AM-5:30 PM with Sundays off. It’s fine by me. I rush out to pick up my linen bag before the laundry closes—sheets, pillow, quilt. For whatever reason I spend the next hour making myself at home by unpacking my things in the tiny space. Maybe it’s because I know I’ll be working the next day and I’m a little nervous about doing a good job. It’s been a long time since I was in a professional kitchen. I’m eager to impress.

Entering the dining room on my first night I’m astonished to see a perfectly gorgeous pile of spinach in the salad bar. Wow! Freshies indeed. I make the big Big Salad I’d been seeking in Christchurch and then find a seat by myself where I can calm down, read and generally gather my thoughts before the whole reality of my life at McMurdo begins. It’s odd being temporary here—I’m just passing through and yet I have to make a life for myself, both at work and in whatever free time I have. I’m determined to make the most of being here, by the ocean, in a place that’s as unknown and marvelously layered with history as anywhere I’ve ever been.

After dinner, I make a detour to go outside for a moment (my dorm room is in the same building as the galley and dining hall) even though it’s something like four below and windy. Just for a second, I want to look out across the ice. McMurdo is on the southernmost tip of Ross Island, sloping down toward the ocean. I stand, shivering without the proper clothing, gazing out over the frozen sea. Spread out in all their splendor beyond the grubby, busy, dirty town are the most astonishing mountains. I’ve never seen the range of blues contained in the soft peaks rising up out of the sea ice. The sun sits low, illuminating the sight, as if from beneath. I can’t take my eyes away.

Perhaps it’s their perfectly unblemished purity that I’ve never witnessed anywhere else in the world—nor imagined I would see for myself. The distant landscape remains entirely unmarked by man—there are no roads, no buildings, no antennae, no humans. It is exactly as Cherry and Scott and Shackleton saw it when they were here, sleeping in the cabin Scott built in 1901 at Hut Point, just a half mile away to my right. I’m transfixed by the transcendent perfection of untouched nature, by the colors, by the softness of the shapely peaks and the plateau above, a downy beauty underscored by the hard blue signaling the severity of the cold.

I might be looking out, across the sound, at the Admiralty Mountains. I’d like to think so. The first sight of Antarctica Cherry saw was of those very same mountains, near midnight, on New Year’s Eve, 1910. As he tells it, his mate Atkinson woke him with a question, “Have you seen land?” Cherry, snug in his bunk, had not, but he dutifully wrapped himself in his blanket and stepped out of the “nursery” (so called because it housed the youngest members of the crew) onto the deck. “And there they were:” he writes, “the most glorious peaks appearing, as it were like satin, above the clouds.”

Wow. Just beautiful --content and prose. Go Cree!!

It’s so exciting to read these posts for others like you, who are lovers of this place