2024: More than a Month to go but I'm Already Thinking about the End of (my) Days at the South Pole

I’m now closer to the end of this cold, crazy adventure than I am to the beginning. The only guy on station who has been here since winter says there are 38 days left. (Poor guy has been counting for quite some time now, I’ll take him at his word.) As the sun drops closer to the horizon in the next ten days, as my already gargantuan shadow grows longer, I’ll be watching the temperature rapidly decline. By mid-February, according to my friend the meteorologist, the Pole will return to temperatures in the minus forties. Today it’s a mere twenty below; I don’t even feel the frost on my face.

The pretty little Baslers do not fly well below minus forty and below minus fifty it's something of a no-go. That means that every year there’s a hard deadline for the last flight out: February 15th.. Most of the bodies on that final plane will be firefighters since every time a C-130 takes off or lands they are on the runway in case of disaster. (This is not a comfort to me. Maybe it should be.)

Right now, the station is still in summer mode with a full population of 141 bodies, with another dozen in from McMurdo two days ago after repeated weather cancelations. I’m waiting for the population to thin which equals less work for me. Baking for 141 is essentially the same as baking for 70 but these numbers are sneaky. I want to be making five times the recipe, not twelve. (My tasty invention: S’mores cookies made with chocolate, crushed graham crackers and marshmallows which I delivered hot to the very chilly New Year’s BBQ.)

Sometime in late January, the winter-over crew will begin to arrive and the summer crew trickle out. There are certain people I look forward to seeing in their full-ECW (extreme weather gear) waiting at the DA (Destination Alpha; DZ —Zeta— is below The Most Beautiful Freezer in the World) entrance for the flight back to McMurdo. (Did someone say good riddance?) Others, I’ll be sad to see in their Big Reds, marching across the squeaky snow toward the roar of the waiting C-130. By February, I’ll be waiting for word of my replacement since my departure date depends on when that person arrives and how much, if any, overlap I need to train them. Most over-winters at the Pole are experienced so I suspect it’ll be a quick hand-off.

I don’t have firm numbers, but the majority of people currently on station are not wintering over. If I had to guess, I’d say about twenty people have winter contracts here and maybe another twenty have contracts at McMurdo. (I was offered a contract but home beckons.) Both stations keep a winter skeleton crew although McMurdo’s is much larger, somewhere around 130 compared to the 43 bodies who will remain isolated here from February 15 through the first flight in, sometime at the end of October. It’s a long time and honestly, having spent two months here, it would take a great deal of cash plus a change in occupation to induce me to stay the winter.

That said, those who do stay have a month of twilight to look forward to after the sun dips below the horizon on March 22. In the days leading up to the 22nd those on station will be treated to a week-long sunset as the sun skims the horizon for days in a row. Next are the auroras and the stars and the moon reflecting off the snow. Still, the over-winters are stuck here with the same people for eight and a half months (!) without freshies other than those grown in the greenhouse. (Below is my first, possibly my last, freshie salad from the South Pole greenhouse.)

Even if we pretend, for the sake of argument, that I didn’t miss my husband, kids, friends, dog and the great city of New York, I’ve learned that working in the galley, either as a steward or cook, is the worst job in Antarctica. Galley crew work longer hours for less money than anyone on station and, to top it off, they’re stuck inside. While I frequently put in twelve-hour days, most people here work a fairly relaxed ten-hour day (or less!), one that includes an hour and a half of breaks not to mention plenty of down time when there’s either not much work to do or what work there is can easily be put off. The galley is where a great deal of sitting, chatting, drinking coffee, munching puck cookies and shooting the shit done by both scientists and Ops. I work and watch from the kitchen.

If I ever return to the Pole it would be as the head of water quality control/power plant observer (the job requires wandering the building taking samples from the taps, reading, sleeping and eating) or even a job in waste that involves being inside and outside, driving cute little ‘dozers with a tad of desk work thrown in for adequate cocoa-drinking time.

I’m not saying people don’t work hard here. They do and many endure grimy, cold, physically demanding jobs. The mechanics and what are called “fuelies” come to mind. (The fuelies re-fuel the planes, bulldozers, and other vehicles while also somehow supplying the building with the loads and loads of special jet fuel necessary to heat it.) These people keep their gasoline-soaked boots outside their rooms, filling the corridor outside my room with a Texaco vibe.

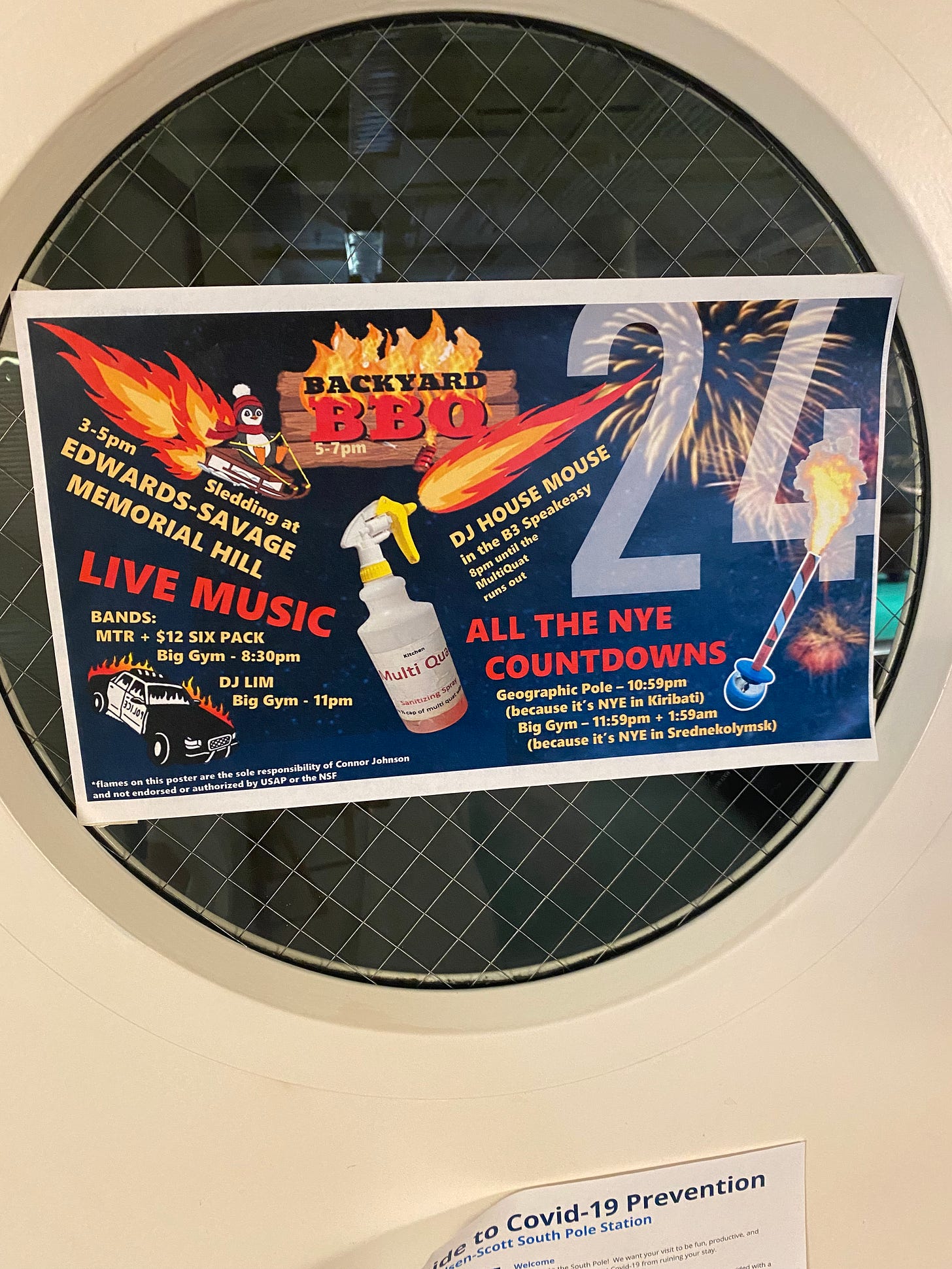

Galley is the lowest status job on station, with NSF scientists or “grantees,” as they’re called, the highest. The two intermingle but not more than necessary. The hierarchy is unmistakable, whatever claims of grand equality Anthony Bourdain proclaimed in his Antarctica episode of Parts Unknown. I have noticed more mixing has begun to take between the two groups as the winter-overs seek one another out, separating themselves from the rest of the crowd as they invest in their future social lives. (Solidarity won’t save them.) All that said, the most I’ve seen the whole station mix was New Year’s Eve when, for a change, even the galley crew participated in the festivities thanks to an all-station R&R day. Burgers and ribs were unearthed from the cavernous freezer below the beer can (see previous post) and a grill, ice bar and tables were set up outside. The center of this New Year’s Eve celebration was the giant pile of bulldozed snow that was constructed for the sole purpose of sledding.

Adults get more excited about sledding than you might imagine. I know I did. In a place as flat as anywhere on earth in every direction, the mound of snow that constituted the sledding hill was a novelty. I’d never seen the station from such a height—although my friend, a pilot from Kenn Bork Air, shared a cool photo of the station he took from the air. (Bottom of the post.) It turns out, not surprisingly, that a cookout at seventeen below zero makes for chilly fingers. It’s somewhat impossible to eat with gloves on and the pinky finger is the first to freeze. The food also freezes faster than you can eat it. Some guy behind the ice bar dispensed a vodka, Kahlua and orange juice cocktail while the wiser imbibers mixed and brought their own. All those bundled bodies walking around with Klean Kanteens and Yeti thermoses were not exactly hydrating. A great many hot toddies and other warm alcoholic beverages were consumed that day. Even I had one, made with the last of my Christmas baking rum. Tasty!

The highlight of the New Year’s Eve holiday was seeing the IceCube facility and the two telescopes. I’m unqualified to properly explain the science going on in the three buildings. Both the telescopes scan sectors of the universe (going around the Milky Way which just makes it hard to see) for evidence of the origins of the universe. This involves measuring tiny gravitational differences that are fully beyond my grasp. The work the IceCube scientists are doing is even more complicated, involving as it does quantum physics. Despite this, it’s somehow more immediate or maybe the scientists are simply more accessible.

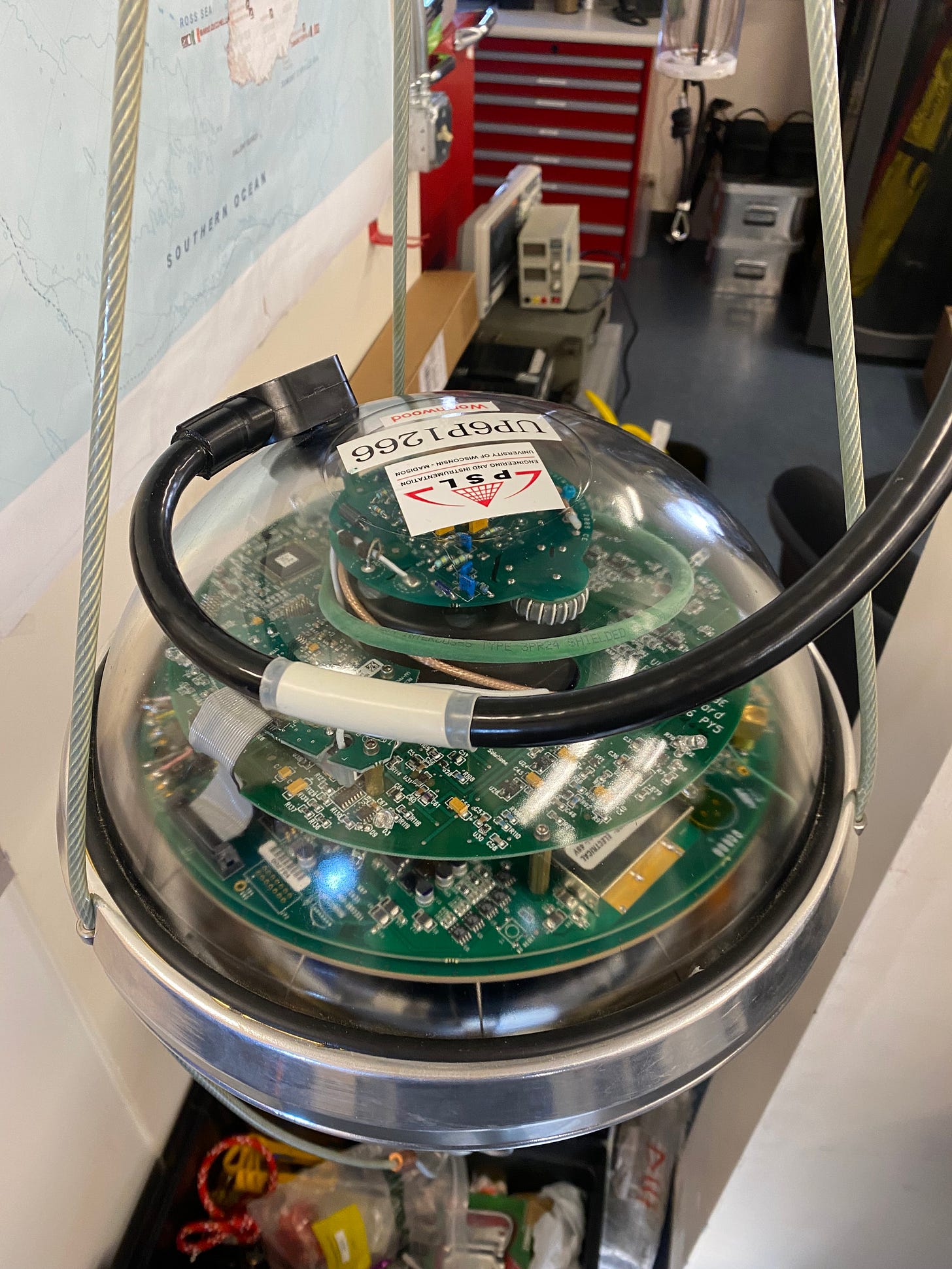

The probes the IceCube team set deep in the ice detect neutrinos which are invisible and virtually undetectable particles of energy/matter. The ice, as I’ve noted previously, is both dark and quiet in every sense which means the probes the scientists drop down deep (over a mile) into the ice can detect the presence of neutrinos. Most amusing: each of the probes has a name—I’m told numbers were too confusing and difficult to remember. The names make referring to a specific probe—one that’s producing good data, malfunctioning or otherwise unremarkable—easier. The list, a borrowing of any number of taxonomies plus random words and names, amuses me. The probe below, which failed before it went in the ice, is called West Virginia. (I did not make that up.)

It’s been a busy, comparatively relaxing few weeks since the bustle of Christmas. As the end inches closer I’m aware I haven’t done everything I wanted to at the South Pole. There’s still time. Two of the key items on my list: a tour of the ice tunnels that go for something like a mile below the station and a long walk or ski to a point where I can’t see the station or any flags or people or buildings. I should manage to accomplish these goals before I leave—and more. Still, I hope my replacement baker has already PQ’d and passed his or her security clearance so I can move my life along. I dream of home as I imagine myself arriving back in the warm, scent-filled air of Christchurch, New Zealand where it will be early fall, the Botanic Gardens in full flush, and all the good coffee, wine, steak and freshies I can imagine there for the taking.

I was waitlisted as a galley assistant 22 years ago and didn’t get the job but sorta wondered whether it would be difficult for the reasons you mentioned. Thank you for answering my questions from all those years ago! Looks like a lot was experienced by you. Thank you for your lovely writing.